Sending your story to an editor—especially if you’re new to the process, but also when you’ve been writing a long time—can induce anxiety and above all, uncertainty. What’s going to happen? What shape will the manuscript be in when you get it back?

Here’s a behind-the-scenes look at my editing processes. First, I’ll talk about how I make suggestions. In two follow-up posts, I’ll discuss the kinds of suggestions I most often make.

You may find this series offers a useful checklist for your own self-editing. I encourage every writer to practice editing their own work—it develops your voice and strengthens your writing. (Sometimes people ask me, “Aren’t you afraid that if every writer could edit themselves, you’d be out of a job?” Not at all! Self-edited manuscripts are wonderful because I can help the author with richer aspects of craft. They have greater clarity on the story they’re telling and confidence in their work. As for my job security, writers hire me because they know, once they’ve finished their revisions, there’s no substitute for a fresh, educated, and experienced perspective.)

This three-part series on editing is especially made for those who like to have a lot of information about what to expect. You can read a shorter description of my process and services on my editing page. And remember, you can always find out firsthand what my feedback on your writing will be like by filling out this form for a free sample edit on 1,000 words.

What will my manuscript look like?

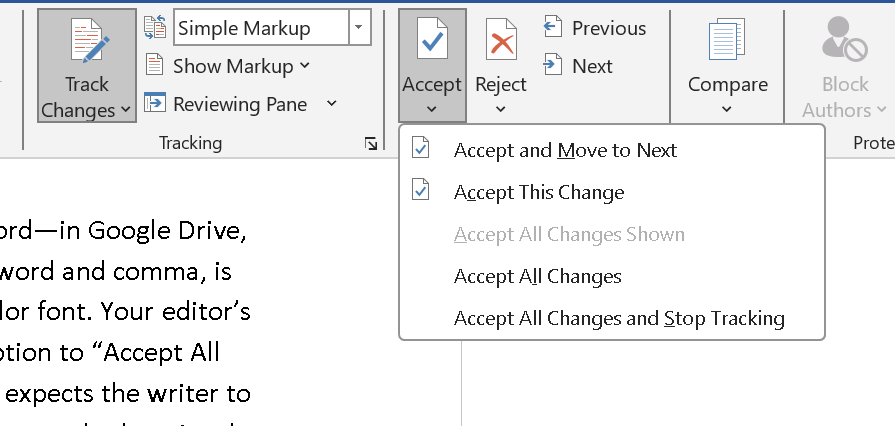

First, to get briefly technical: for line-by-line editing, I use Tracked Changes in Microsoft Word (in Google Drive, it’s called “Suggesting” mode). This means the original version of the text is preserved, while my suggested changes appear alongside it in a different color. These suggestions won’t be finalized until and unless you “Accept” them.

Microsoft Word offers the option to “Accept All Changes” in the file with one click, but I’d rarely recommend this. No editor expects the writer to agree with them on every suggestion. And you might agree with me that a sentence should be changed, but have a different idea about how to change it. So even when there are many suggestions, it’s worth taking the time to review each one. This process can even fire your imagination, giving you more ideas for where to take the scene or story, and it’s educational, too (for instance, being line edited myself is how I first learned what an Oxford comma is and just how often I use em-dashes).

Microsoft Word also offers the option to view “Simple Markup,” which presents the manuscript as it would look if all Tracked Changes were accepted. This can be useful to check the flow of a change you’re not yet sure you want to keep. (But if you’re not seeing the edits you expected, make sure you’re in “All Markup” view with “Show Comments” selected!)

In addition to in-line Tracked Changes, I use comments to explain why I suggest a change, to ask questions, or to offer other options. For example: “Susanna already shook her head on the previous line. Here, should she refuse Joshua’s request in a different way, such as by saying ‘I can’t’?” or “I expected Susanna to agree to Joshua’s request because she shares his goal of helping Carrie win the spelling bee: why does she refuse?”

Explaining my changes can help authors understand what to do in the future (for example, how to avoid dangling modifiers). The explanations also guide you if you’d prefer to rephrase in different ways from my suggestions.

So, when it comes to what shape your story will be in when it comes back to you from the editor: the same shape it was when you sent it off, with some added TLC.

Therese’s editing approach

Each editor works a little differently, but here’s how I do it:

I always make at least two passes through a manuscript. On the first pass, I read to learn what happens in the story. I use comments to make notes to myself (for example: “Is this foreshadowing?” or “Double-check her motive for this” or “This word is used a few times; repetition effective or distracting?”). If I’m doing a line-by-line or copy edit, I’ll make immediate Tracked Changes corrections to misspellings, some grammar, some awkward phrasing, and some repetition. Sometimes, I mark repetition or redundancy by highlighting the two uses of a word/phrase/idea. It’s up to the author to decide which to keep and which to remove or rephrase. At other times, when one instance stands out to me as much more or less necessary than the other, I suggest a change myself.

On my second pass, now that I know how the story turns out, I’ll follow up on my notes, write comments directed to the writer rather than myself, and make more detailed line-by-line suggestions. When I deliver a line edit, my ‘cover letter’ in the email summarizes key points and pieces of advice that apply most frequently in the manuscript (e.g. “I often suggest breaking up a long sentence so the action is easier to follow”).

If I’m doing a developmental edit, I’ll leave fewer comments and line-by-line suggested changes. I’ll offer grammar corrections, but mostly as examples for the author to look into further down the line. My priority is writing a four- to eight-page memo with my advice for plot arcs, character development, and other elements of the story. This goes much deeper than the line-by-line ‘cover letter’ and is often broken into subsections (which sections will depend on the needs of the story). The memo can also include stylistic advice and grammar advice, but the developmental edit is more focused on overall story shape and events rather than the phrasing of individual sentences.

Timing and other expectations

Unless exceptional circumstances require a rush, I try to sleep on every edit before I deliver it, or at least to take some time away from my desk to let my subconscious work. A question or idea often arises when I’m not thinking directly of the project.

You’ve probably found this is true of writing, too!

Both writing and editing benefit from sustained attention, but focus clouds and productivity drops if you work too hard to for too long. I try to take breaks every hour or ninety minutes to rest my eyes and move my body.

Additionally, my workday is not solely dedicated to editing. Like most editors, I bill between 2 and 4 hours of editing per day (3 hours is my average goal). The rest of my time in the office is spent on administrative tasks, including managing invoices, writing blog posts, and reading about the craft and business elements of writing and editing.

Combining both my first read and second pass, I line edit between 1,100 and 2,200 words per hour. That’s a wide range because it depends a lot on the needs of a particular story. Looking at the upper end, you might initially expect an 80,000-word story to take 40 hours to edit, and thus to be completed in a single 40-hour workweek. In rare circumstances, I might do this to help an author meet an impending deadline, but it’s far from ideal. Usually the 40 hours would be spread across two weeks or a month. (In addition, I often balance several projects at once, of different sizes and in different genres.)

One thing I do that you shouldn’t expect of every editor is work on weekends. Not every weekend, and not all day, but I often sit down for an hour or half-hour each morning to work on a project. This is because, though I only have so many hours of intense focus in my each day, I have those hours most days (barring illness, special occasions, or classes and volunteer commitments that take me out of the office). This helps me keep steady progress.

And the flexibility to step into my home office and work whenever I feel like it (or step away when I need to refresh my brain and body) is a major perk of running my own small business.

Related to focus, the need for rest, and the fact that I do multiple passes of each manuscript: writers are sometimes embarrassed and chagrined when the manuscript they self-edited comes back with corrected typos that slipped past them. Don’t be embarrassed. Typos are sneaky little things, and you can only stare at the same sentence so many times before you start to read what you expect it to say, not what it actually says. We’re all only human.

That’s true of editors, too. Our goal is to get between 95% and 99% of all errors in the manuscript. So, after the copy edit, the manuscript should also be proofread—and ideally, I’d recommend hiring a different person to proofread than did the copyediting, or at least letting some time pass between the two drafts so that the editor’s eyes are refreshed.

The fewer errors that are in the manuscript in the first place, the better the odds of editing making it nearly error-free. (If you send a manuscript with 100 errors and editing catches 98% of them, you’ll only have two errors left. If you send a manuscript with 1,000 errors, catching 98% of them will leave you with twenty errors left.) This is why I encourage editors to develop their self-editing skills. In addition to self-editing and professional editing, a crew of keen-eyed beta readers can help clean up lingering typos.

Some authors and publishers have the resources (both time and money) for multiple passes of editing. Some can only prioritize a few. I encourage authors to take quality seriously. At the same time, don’t beat yourself up if the occasional typo makes it through. Reread some of your favorite authors and you’ll probably notice a rare mistake in their text, too. We want to prevent it as much as possible, but when a story is overall well written and presented in a professional manner, readers will forgive minor issues. They’ll be able to see that you and your team have done your best.

In my post next week, I’m going to talk in more detail about line-by-line editing and copyediting (or copy editing).

Therese Arkenberg's first short story was accepted for publication on January 2, 2008, and her second acceptance came a few hours later. Since then they haven't always been in such a rush, yet her work appears in places like Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Analog, Daily Science Fiction, and the anthology Sword & Sorceress XXIV. Aqua Vitae, her science fiction novella, was released by WolfSinger Publications in December 2011.

She works as a freelance editor and writer in Wisconsin, where she returned after a brief but unforgettable time in Washington, D.C. When she isn't reading, writing, or editing (it's true!) she serves on the board of the Plowshare Center of Waukesha, which works for social, economic, and environmental justice.

Therese Arkenberg's first short story was accepted for publication on January 2, 2008, and her second acceptance came a few hours later. Since then they haven't always been in such a rush, yet her work appears in places like Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Analog, Daily Science Fiction, and the anthology Sword & Sorceress XXIV. Aqua Vitae, her science fiction novella, was released by WolfSinger Publications in December 2011.

She works as a freelance editor and writer in Wisconsin, where she returned after a brief but unforgettable time in Washington, D.C. When she isn't reading, writing, or editing (it's true!) she serves on the board of the Plowshare Center of Waukesha, which works for social, economic, and environmental justice.